By David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/21/2001

NEWPORT, R.I. -- It's a decade from now in the choppy seas off the Korean peninsula and a US carrier battle group is steaming into the area to engage the enemy.

But there's a hitch. The most potent sea force in the world can't get close enough to use its arsenal because the coastline is too dangerous.

In the war against Iraq in 1991 and the air campaign eight years later against Yugoslavia, the Navy prowled the seas with little to fear except a few old sea mines and some clunky submarines. A decade into the 21st century, however, no hostile coast is safe for a hulking US armada worth tens of billions of dollars.

The problem is that nearly every country in the world that wants them now has inexpensive sea-skimming cruise missiles and access to commercial satellite photographs. That means huge, slow-moving targets like aircraft carriers and other ships that carry thousands of sailors are relatively easy targets.

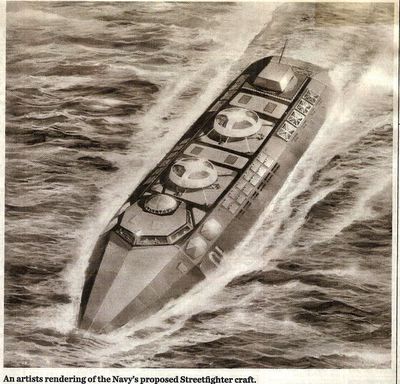

Enter the Streetfighter.

A year after its debut in the highly classified annual war games held in Newport in the windowless rooms of the Naval War College, the small, speedy ship packed with missiles and spy sensors is being hailed by some top officers as an antidote to what they call in Pentagon parlance "tactical instability."

In a mock war staged last month in Newport - where hundreds of top Navy officers and observers battled each other in a conflict paralleling potential clashes with countries such as Iran or North Korea - the new breed of ship called the Streetfighter stood out as a contrast to the steadily corroding power of today's force of cruisers, destroyers and carriers.

As underscored by the bombing last year of the USS Cole in Yemen, in which 17 sailors died, a crude inexpensive weapon, let alone a more advanced cruise missile bought for less than $1 million, could easily destroy ships worth nearly $1 billion.

Streetfighter takes advantage of a new revolution sweeping the Pentagon - the ability to use information from multiple sources so soldiers or sailors across a battlefield can look at the same picture and help target weapons from hundreds of miles away. Its supporters envision the program as a networked fleet of small ships operating as a single force.

"To correct for this tactical instability, we can now spread the capability of one of today's ships across 10 ships," said Vice Admiral Arthur K. Cebrowski, the president of the Naval War College and chief promoter of Streetfighter. "That makes it much harder to target; the enemy has to use 10 missiles instead of one."

The Streetfighter - along with a slew of other conceptual weapons ranging from small, stealthy aircraft carriers to unmanned ships - still exists only in the minds of men like Cebrowski. But it is in line with the vision of President George W. Bush, who, in Norfolk, Va., earlier this year, called on the military to "design a new architecture" that would "move beyond marginal improvements to harness new technologies that will support a new strategy."

To Cebrowski and other proponents, Streetfighter, and the information network it would use, is an innovation similar to the introduction of the aircraft carrier or the replacement of cavalry with tanks. Its role would be varied, and would include antisubmarine warfare, land attack and surveillance.

But its main benefit, they say, is that its capabilities are spread across a squadron of ships. If one is lost, the group can keep fighting.

"It's enormously demoralizing to lose a Goliath system," Cebrowski said. Unlike today's risk-averse Navy, he said, future officers wouldn't have to worry as much about losing trophy targets that could trigger the kind of public pressure that ended the 1994 US mission in Somalia after TV showed soldiers being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu.

But not everyone thinks the Navy needs the kind of technological leap the Streetfighter represents. Critics of the Streetfighter - which recently received money for its first prototype and could get a boost later this month when Cebrowski is likely to be named the Pentagon's czar of military transformation - believe the ship would instead hamper future officers because of its inherent vulnerability. Expected to cost about $100 million apiece, the dozen or so small ships operating along enemy coastlines would be well within the range of enemy fire. In fact, critics suggest, they're designed to be expendable.

One top Navy commander who might have the power to ensure Streetfighter never gets off the drawing board is the man recently named deputy chief of Naval operations for resources, requirements, and assessments. Vice Admiral Michael Mullen, formerly the Navy's director of surface warfare and commander of the US 2nd Fleet, has drubbed the idea in Navy conferences and recently told the Wall Street Journal: "I look at the Streetfighter concept and worry that we are saying, `It's OK to lose ships.' "

Other critics blast Streetfighter as a potential boondoggle that has so many contradictions it will never float beyond the prototype phase. The smaller it gets, the less firepower it can carry, they say; the bigger it gets, the less speed it will have. The low cost of the ships is also something of a chimera, they say: Streetfighters will require a large mother ship to ferry them to trouble spots and they will need sufficient protection to withstand hits from helicopters and small fire that might otherwise easily sink them.

Bureaucratically, others add, Streetfighter also must overcome concerns that it would suck money from established programs such as the DD-21, the Navy's next-generation destroyer that's expected to cost as much as $1 billion per ship.

"It's just dumb," said Norman Friedman, a naval historian and author of "The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapons Systems." "It's a farce, or to be kind about it, a self-deception. Small ships are sexy, but they never tend to deliver. And the nondelivery tends to be expensive. Below a certain size, you're basically dead meat."

Of course, Cebrowski and other proponents of Streetfighter beg to differ. They say new ship designs, propulsion systems, sensors, computer networks, and firepower, among other technological leaps, have radically changed the way navies can fight. They also strongly rebut arguments the ships are designed as bait to lure enemy submarines or as a kind of cannon fodder to deplete an enemy's supply of cruise missiles.

As evidence, they cite the success of the Streetfighter in this summer's mock battle at the Naval War College. Although the enemy sank several Streetfighters, observers of the war games say, the small ships complicated the adversary's ability to defend its harbors and mount attacks.

When one diesel submarine successfully torpedoed a Streetfighter, the other ships quickly collapsed on the sub and reciprocated the destruction.

After a while, the subs stopped engaging the Streetfighters. The exchange wasn't worth it.

"There are no American kamikazes," said retired Capt. Robert Rubel, director of research and analysis in the war-gaming department at the Naval War College. "But if you're going in harm's way, you want to make sure one hit doesn't neutralize the capability of your entire force. These aren't designed to be expendable. We're not going to hang anyone out to dry. But the thing is cheap enough, so if we lose it, we don't lose a huge amount of capability."

Like the DD-21, Streetfighter is designed to rely on a smaller crew than traditional warships.

Today's Arleigh Burke-class destroyers require a crew of at least 300 sailors. The new destroyers are being designed for fewer than a hundred. And the Streetfighter is conceived as needing only about 13 seamen.

Still, would anyone in their right mind serve on such a ship, which Rubel and others acknowledge would be far more "risk-tolerant" than any ship in today's fleet?

"That is definitely an issue proponents of Streetfighter have to address," said Ron O. Rourke, one of Washington's leading naval experts and an analyst at the Congressional Research Service. "They're going to have to give the fleet confidence there will be capable people who are willing to serve on them."

For Cebrowski, who's leaving the 117-year-old college next month, the real risks lie in choosing not to take them. He laments a culture in which the threat of a lone mine or missile could force an entire battle carrier group to move, as occurred during the Kosovo conflict when the Navy reportedly lost track of one of Serbia's diesel submarines.

Innovation and the gumption to take risks, he said, are the only remedies to ensuring the United States will continue to dominate the seas, no matter how close to enemy shores.

"History will not reward an officer for slavish adherence to doctrine," he said in a speech shortly after becoming president of the Naval War College in 1998. "In the knowledge age, doctrine which lacks a real-time, dynamic, innovative character will be seen as the refuge of the uninformed. We must do better for our fighting forces."

David Abel can be reached by e-mail at dabel@globe.com.